Nairobi 2032 Olympics – Part 2

The Zeros in the Rings. Re-examining the Nairobi 2032 concept, as we look at the financial viability of hosting an Olympics event.

The outbreak of COVID-19 resulted in many changes for the world over the last few months, and 2020 will definitely go down in the history books as a turning point the world over. This week would have had us all linked and transfixed to our devices as we followed the final events of the originally scheduled 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics.

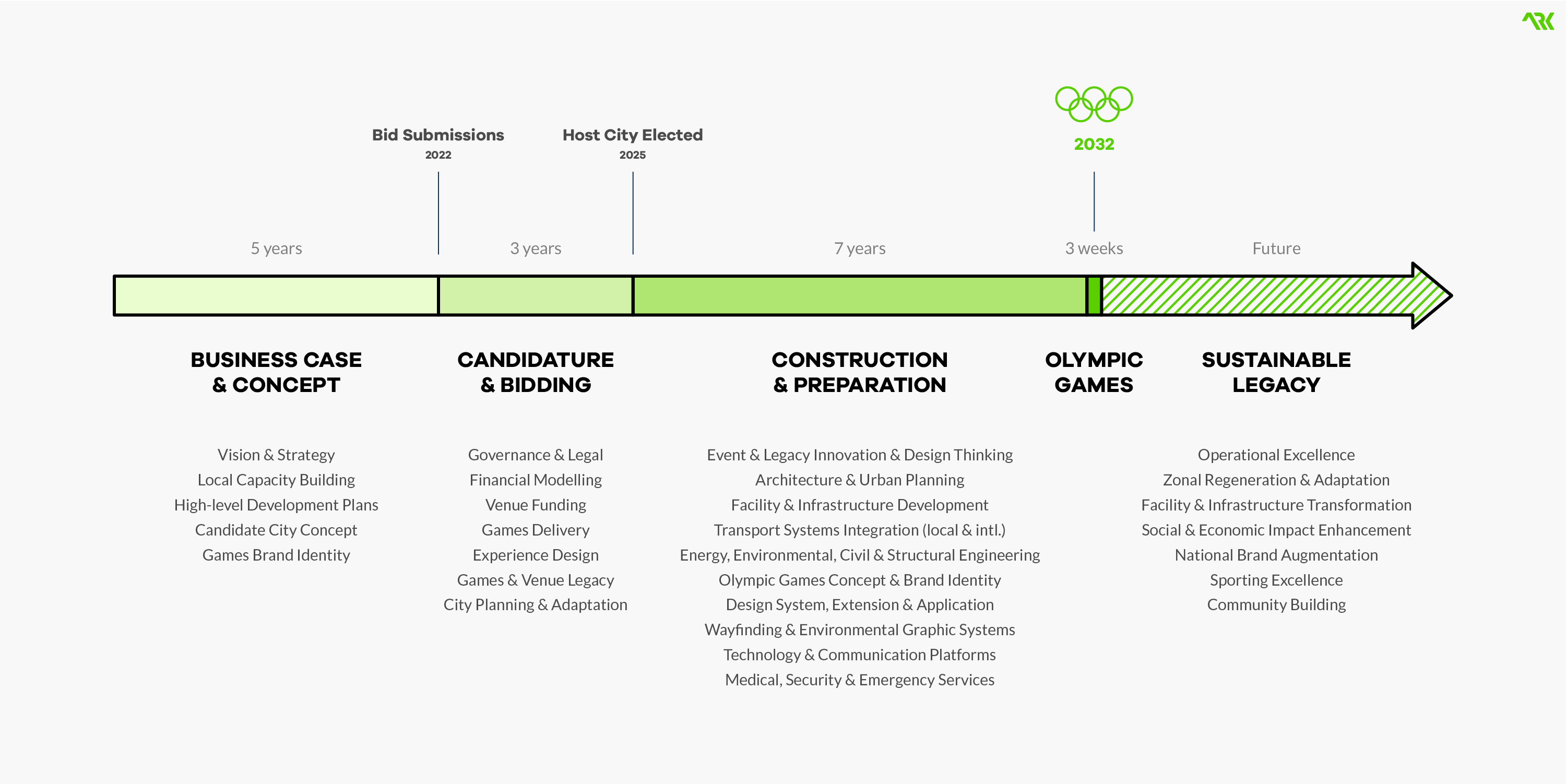

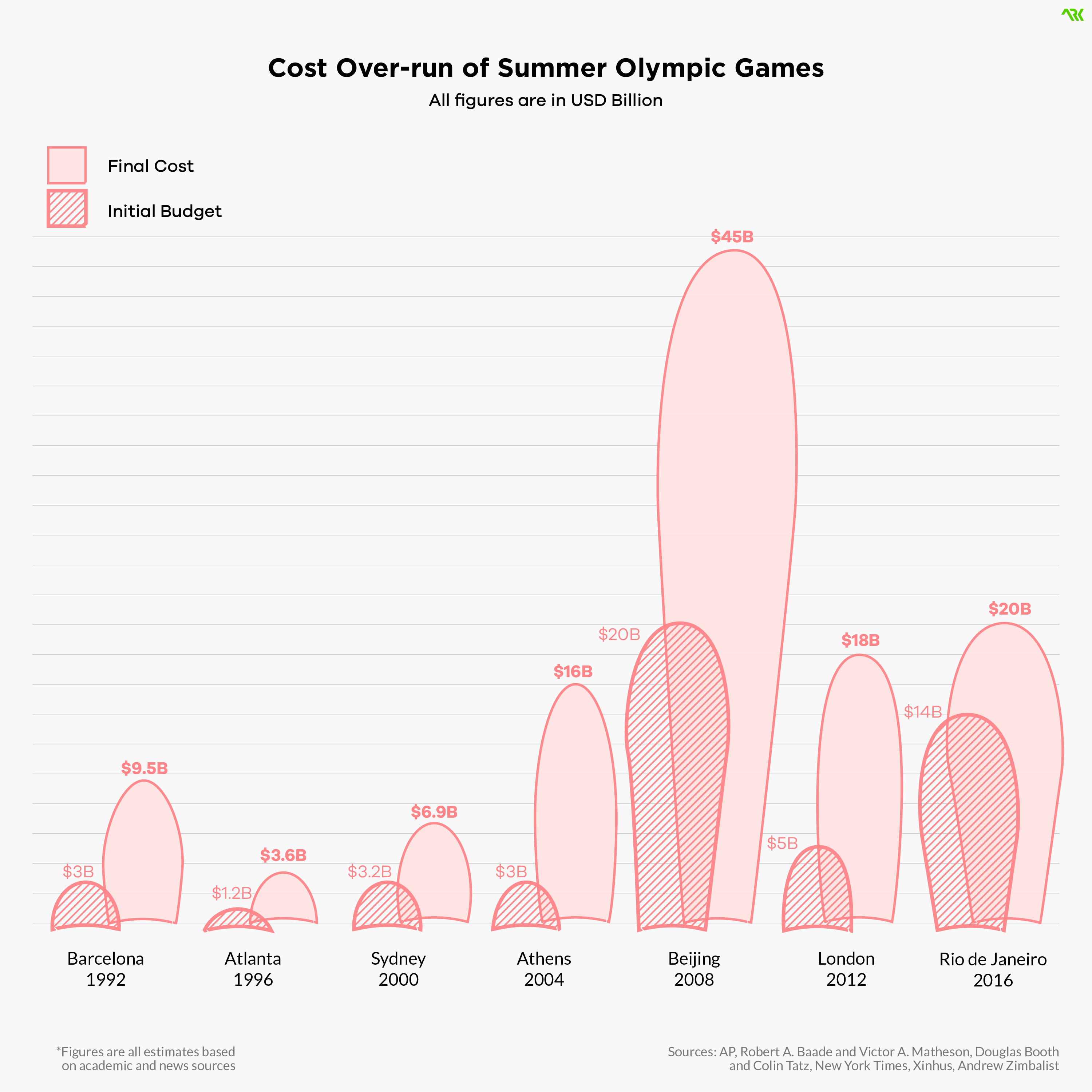

In early March, the IOC announced that the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games shall be postponed to a date no later than the summer of 2021, now scheduled for 23 July to 8 August 2021. A positive decision no doubt but one with large implications for an event that’s already cost around $12 billion to date. As we mulled over this decision our team got to chatting about an idea we’d shared 3 years ago, positioning Nairobi as a potential host for the 2032 Olympics. Our dream was to unite numerous public and private sector teams to work together to show that Nairobi has what it takes, win the bid, catalyse infrastructure development, and deliver a powerful legacy thereafter.

But in light of the recent developments we began to see that there was a large white elephant we couldn’t have foreseen. What if, like Tokyo 2020, Nairobi 2032 had to be postponed due to an unforeseen global or local event? Would our city, its hotels, restaurants & bars, local airlines, partners and insurance firms be able to survive the economic hit? Thinking about this brought us back to re-evaluating our initial idea as we wondered; is hosting the Olympics a worthy pursuit for Nairobi? What is the socio-economic cost of hosting an Olympics? And on the whole, would hosting really benefit Nairobi in the ways that we hope?

Fact Finding

As futurists and lovers of information, facts, and data, we decided to dive into the statistics and figures from past Olympic games. Searching for the positives and negatives from past host cities and reading about the long-term impacts on the cities, their residents and the nation’s taxpayers. The hard numbers we sought were the infrastructure costs, operational costs, and white elephant costs of being a host city, pegged against the revenue generated from the event (excluding any soft power brand equity).

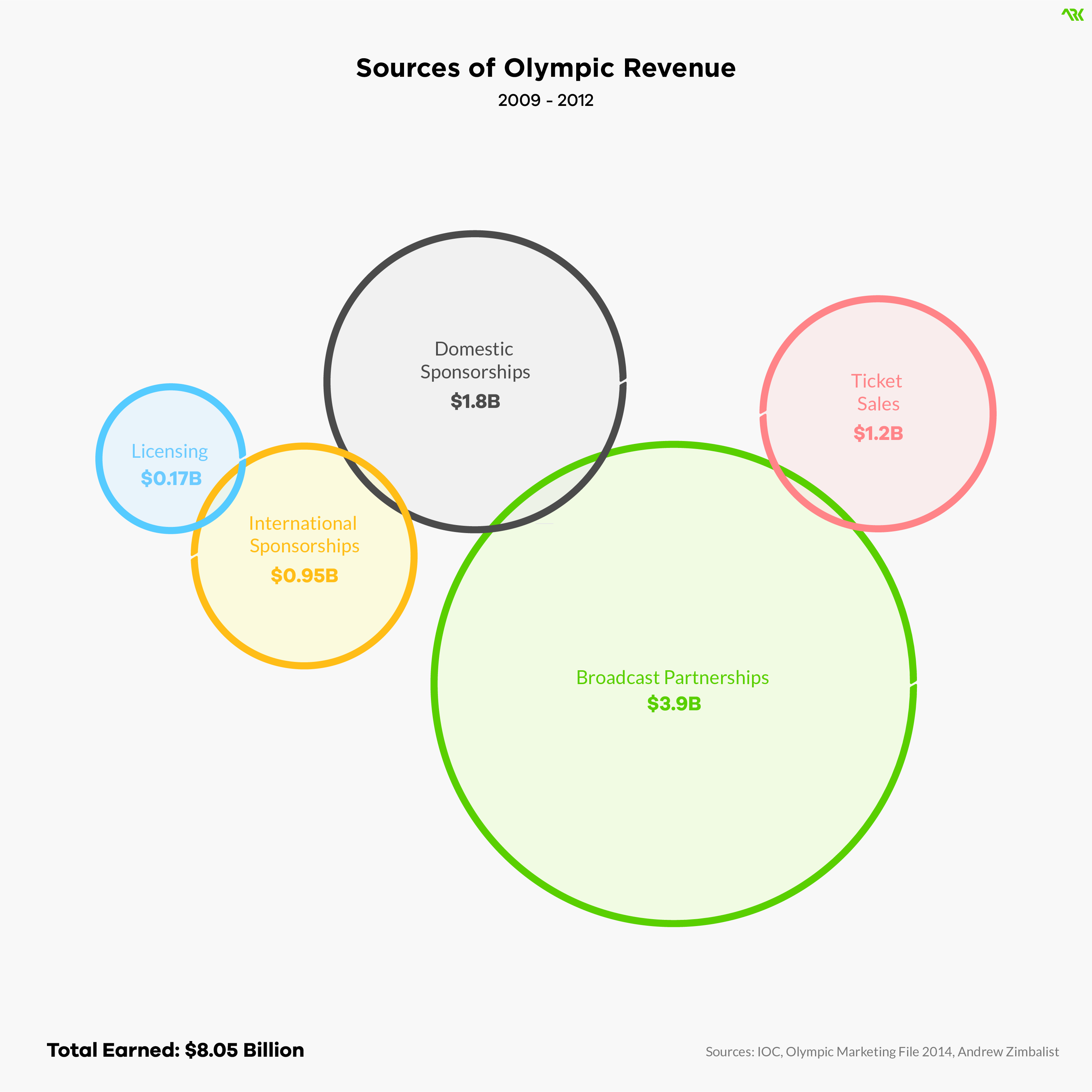

First up was gaining an understanding of how the games earn revenue for the host cities and IOC.

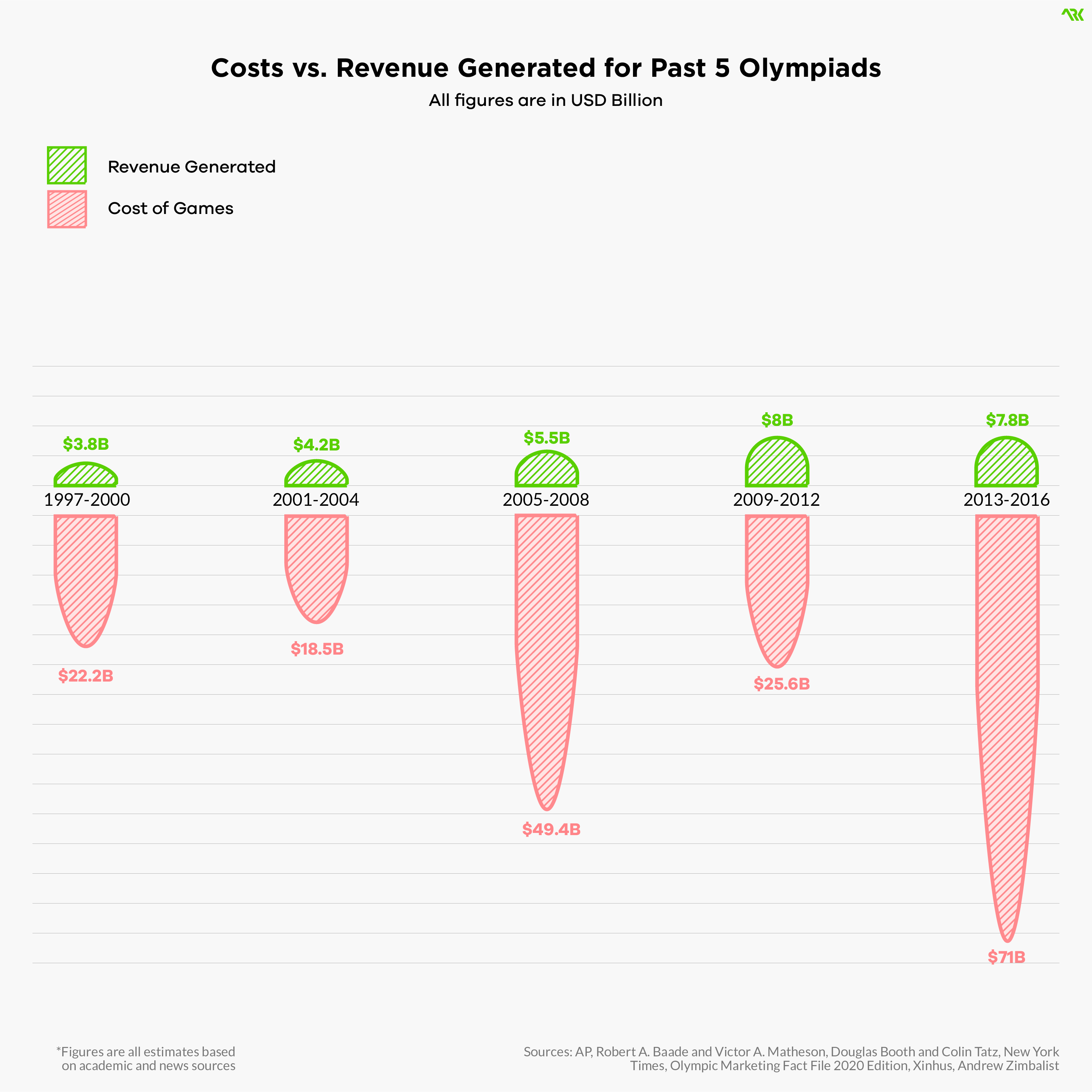

Then we dug deeper to compare the cost vs. revenue generated for the past 5 Olympiad periods.

And here’s how the bid budget and finals costs of Olympics events compare from 1992 to 2016.

Local Residents

The benefits we encountered highlighted that being a host had a much smaller positive impact on local residents than we’d perceived; particularly when we looked at Rio, a city in an emerging economy whose context most closely mirrors our own.

The advent of the games in Rio resulted in forced evictions of thousands of people to make room for the BRT (bus rapid transit), and when the BRT arrived it did little to serve the daily, severe transport bottleneck that local commuters faced, instead catering to the Olympic visitors. Though there was an increase in employment, very few jobs went to the city’s unemployed residents. Instead those with jobs in relevant sectors from within and outside of Rio took up the duty of preparing the city. The promise of better security, safer streets, modern electricity, water and sewerage amenities for low income neighbourhoods never saw fruition. Instead, violence increased, the city’s environmental degradation multiplied, and very few of the city’s residents got to witness the games in person.

The event, however, did result in a 29.3% increase in labour income for the city’s poorest 5%, and though there was a recorded 6.2% rise in tourist numbers, it is unclear whether that number should be attributed to the Games’ participants.

Perhaps, the big question really should be what’s a city’s real measure of success for an Olympics event?

Do the infrastructural investments of the games benefit the city’s residents in the long-run? Is the opportunity cost that sees budgets for other national and city dockets reduced worth it?

TV and media rights are the biggest revenue earners for the Olympic games but over the last 30 years the percentage of revenue the IOC collects from this has grown from 4% in 1990 to 70% in 2016, leaving the city of Rio de Janeiro with no more than 30% share of the TV revenue earned.

It’s time to disrupt the games

Of course it’s too soon to make a call on the long-term impact of the games in Rio but looking at the stats from previous host cities the forecast is bleak which begs the question;

What are some disruptive methods cities like Nairobi could utilise in a bid to become Olympic hosts?

How might we lower the infrastructure, human, and white elephant costs of being an Olympic host city?

Here are a couple of early ideas our team is keen on building further.

- Re-purpose existing stadia facilities.

- Build multi-functional spaces that can be utilised by local residents post event.

- Better align Olympic bid with the host’s infrastructure growth needs.

- Spread the cost (and benefits) amongst several cities by having regional hosts.

Final word

While it is all glorious for a city or country to win a hosting opportunity, it is important that the world comes together at the table and review some of the skewed attendant realities in hosting such an event. Resources are scarcer than ever, soft power and national brand building are diminished in a globally restrained world.

And now, having to deal with COVID19 (thus the postponement of the 2020 Summer Olympics) we will need to learn new ways of handling such events in a way that ensures all stakeholders win, be it in competitions or in economics. The games must go on – or should they?