+HUMAN DESIGN LAB

The Able Cane

Merging accessibility and technology in mobility solutions for the visually impaired.

Background

According to World Health Organisation (WHO), disability affects 10% of every population. An estimated 650 million people worldwide, of whom 200 million are children, experience some form of disability. In Kenya, 10% of the population is disabled, the most afflicted age bracket being children between 0-14 years. Common types of disabilities include mobility (1.16million), visual (0.84 million), cognitive (0.36 million), auditory (0.55 million), and speech (0.45 million)

Inspiration

Curiosity was the mother of our invention. During a casual conversation about the hustles of navigating a bustling city like Nairobi, we began to wonder about the challenge of doing so while disabled. After much deliberation, our curiosity grew to impel the design of a product which could help improve mobility for the blind in our community.

Research and Findings

The backbone to our problem solving is a human centred approach. We always try to push ourselves beyond form and function in an effort to tackle unmet needs. In our opinion, this is how the best inventions are achieved. So, how do you uncover what mobility needs the visually impaired have in a city like Nairobi?

“Ask visually impaired people living in and around Nairobi,” seemed like the most obvious conclusion but it would be at the risk of incremental change rather than a breakthrough solution. While we knew that talking to the visually impaired for perspective on their mobility challenges would be necessary, we also knew we needed more.

A better starting point would be immersion. We conducted an exercise to best put ourselves in the mindset of a blind person. Grouped in pairs, we all took turns to blindfold each other and manoeuvre exiting our office complex. We hadn’t banked on the extent of difficulty or range of adverse emotions experienced during the exercise, especially because it was a space we were so familiar with. It dawned on us that mobility was not only about moving around easily but being able to do so in a calm and confident manner.

Next, we needed to hear the voices and understand the lives of the people we were designing for. We visited Machakos Technical Training Institute for the Blind where we got to shadow and interact with the students on their day-to-day experiences and challenges.

Innovation

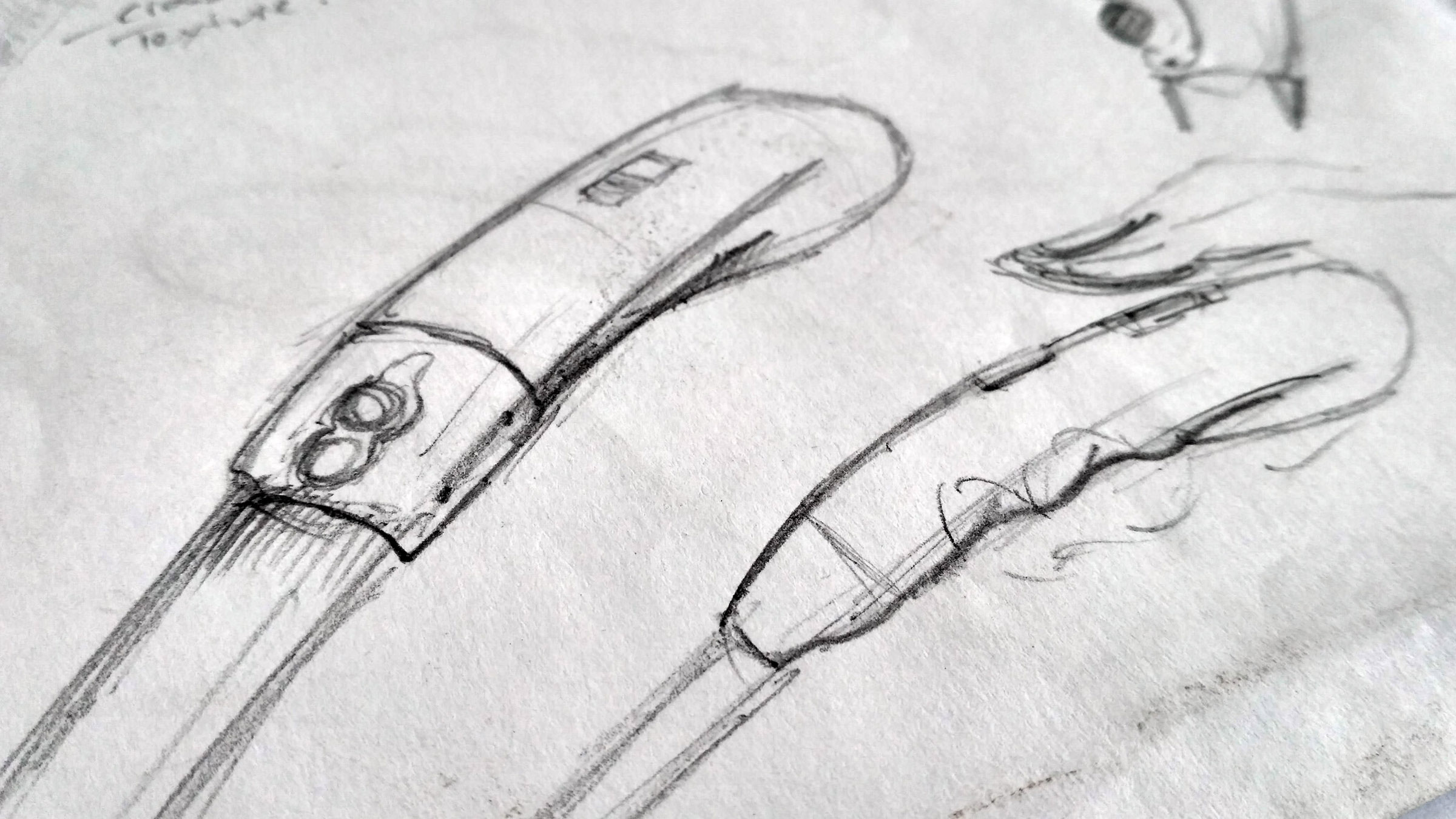

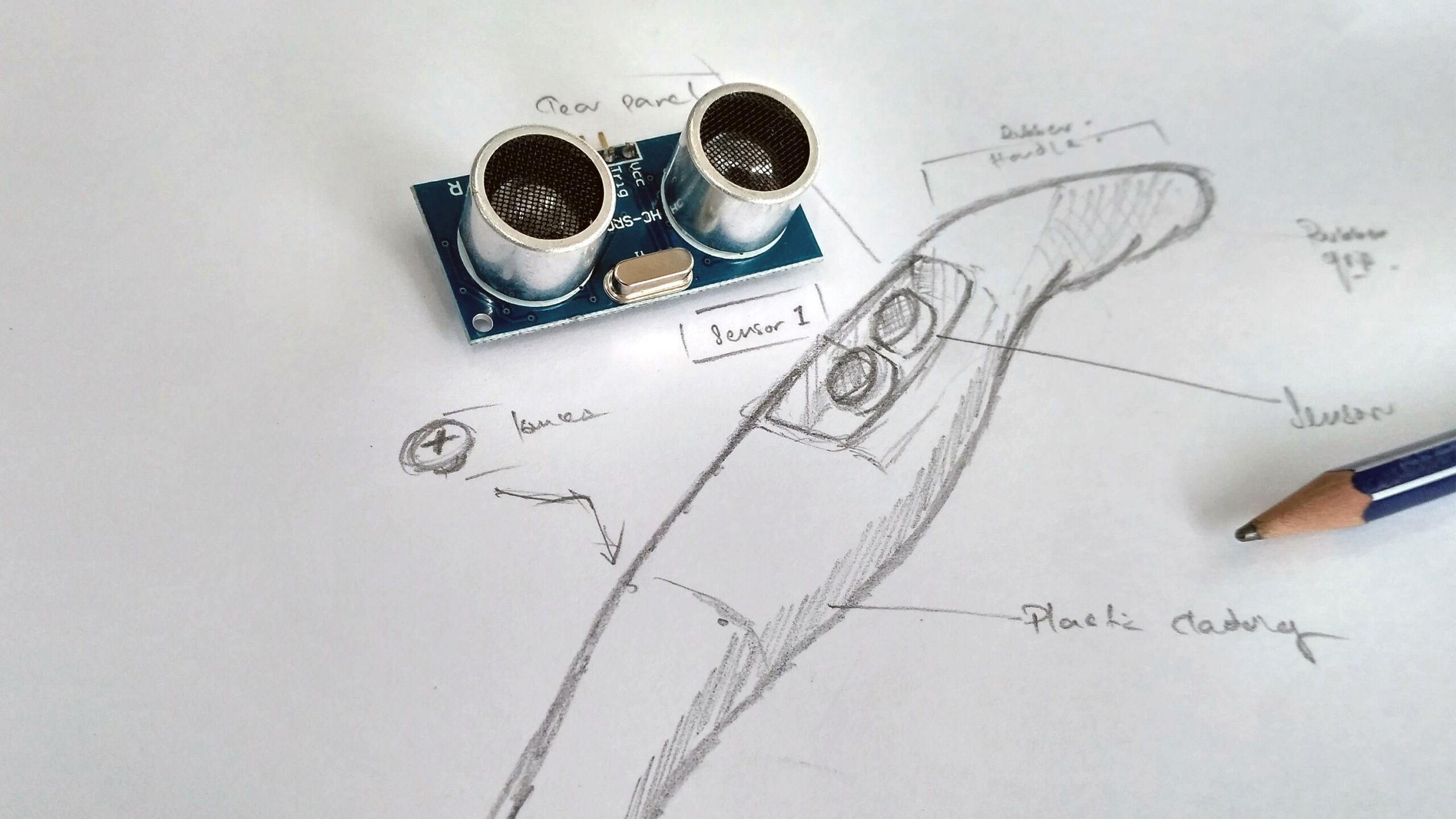

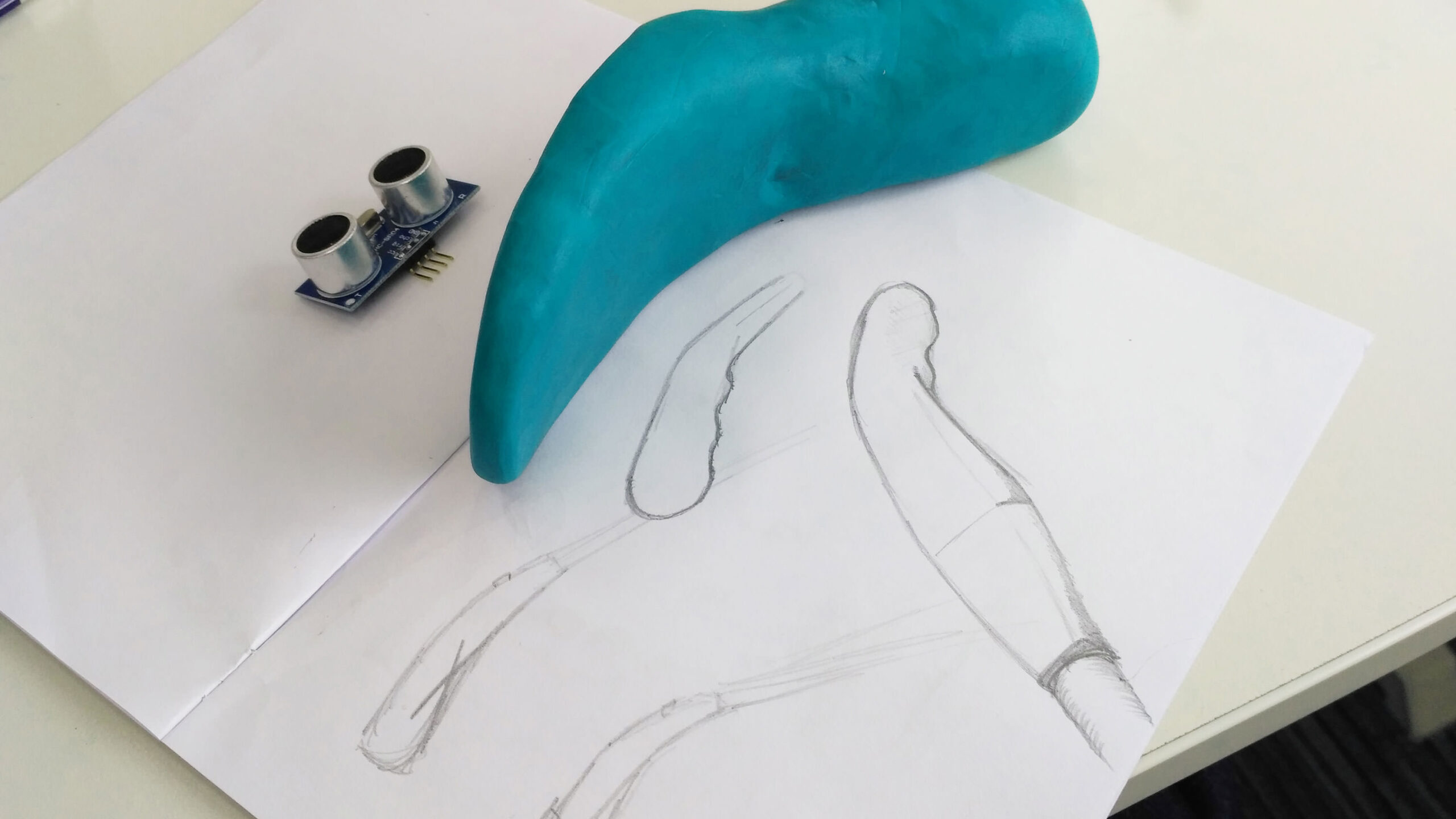

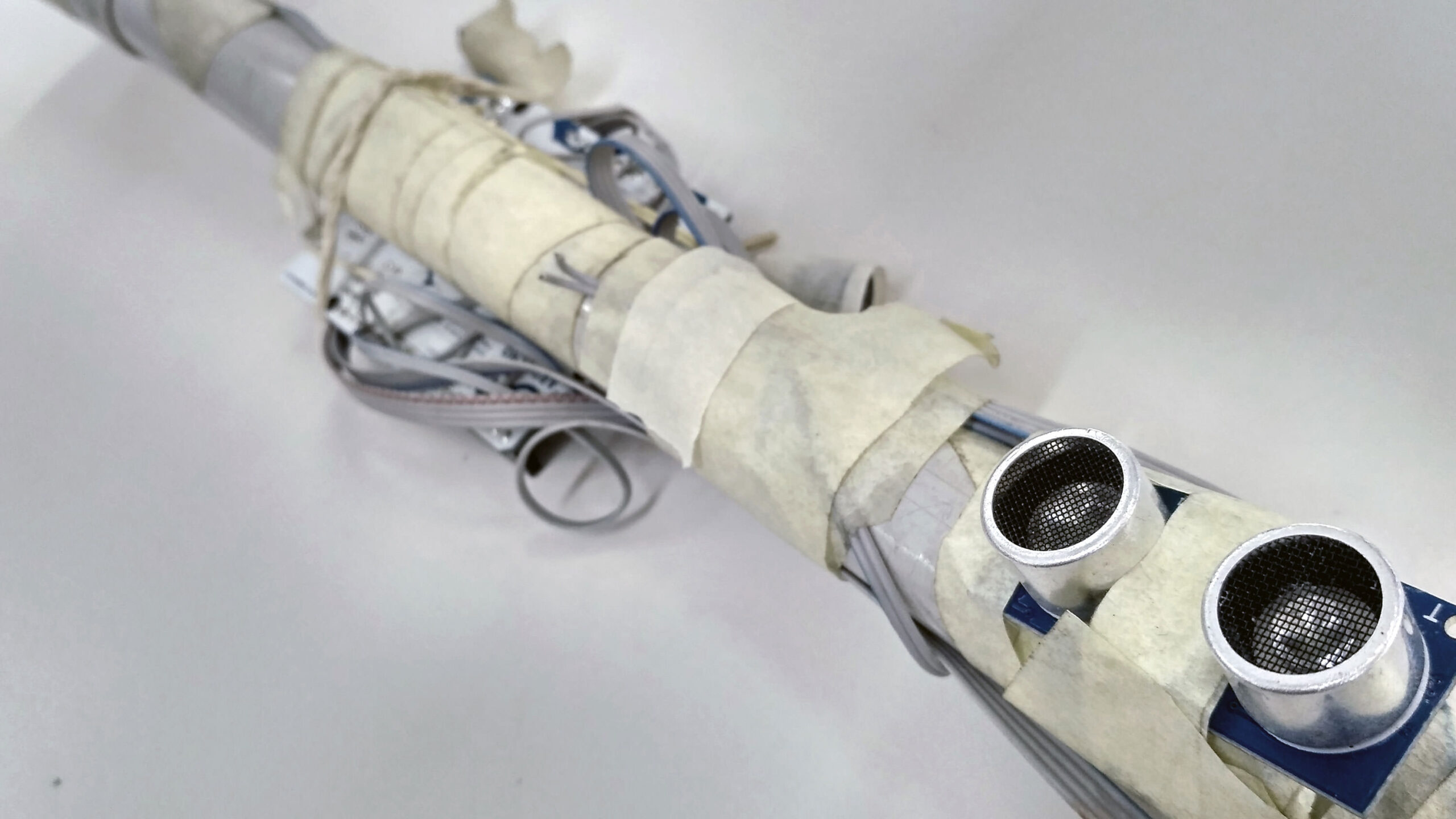

With information from the students from the Machakos School for the Blind, observations, desktop research and our own limited experience, we began to design the Smart White Cane (SWC).

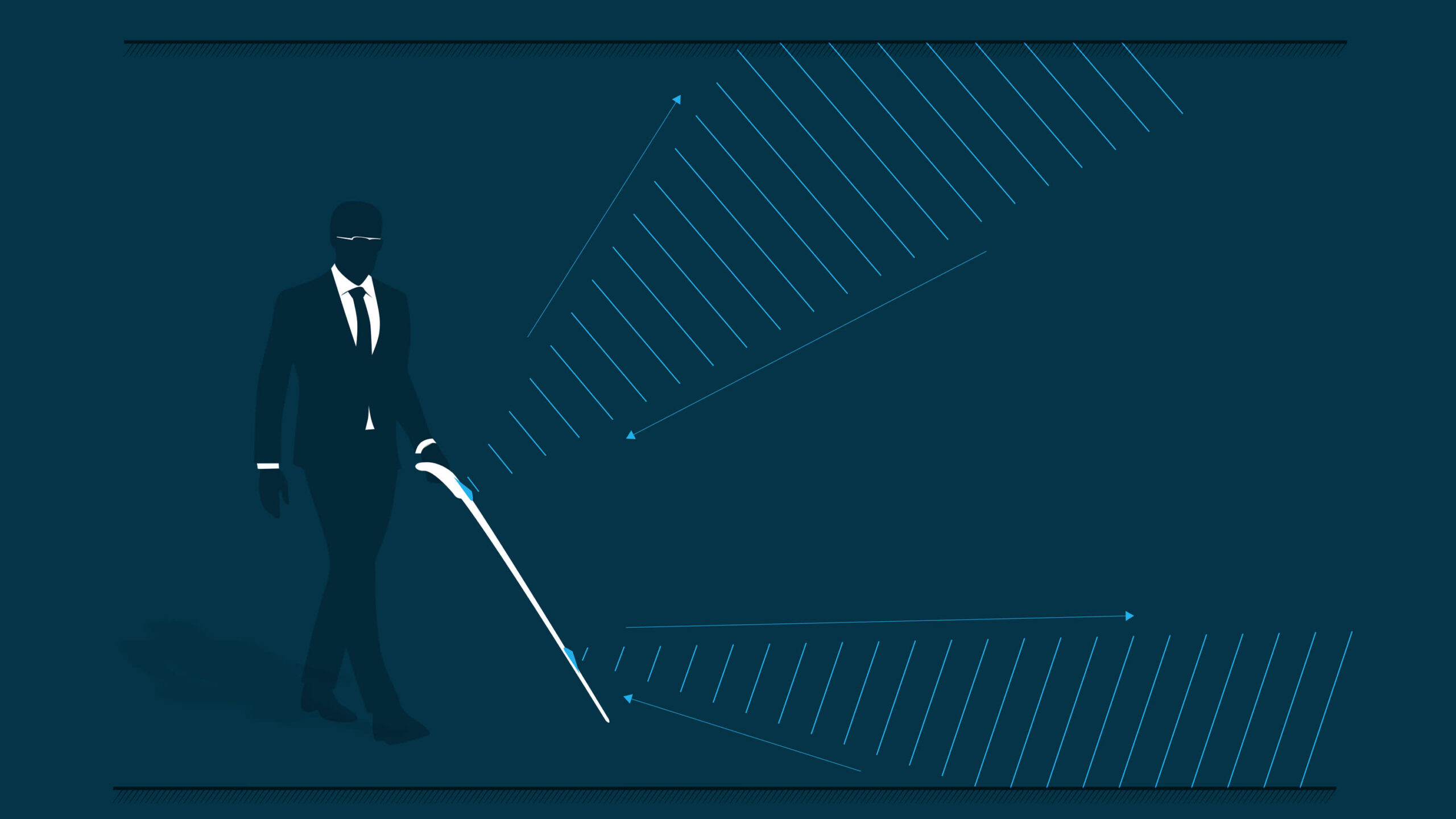

Nairobi is full of surprises, some good and others in the form of unannounced potholes here or a bent street lamp there. Our concept was inspired by the need to help prevent avoidable accidents that the blind are prone to when out and about, by leveraging on their sense of hearing.

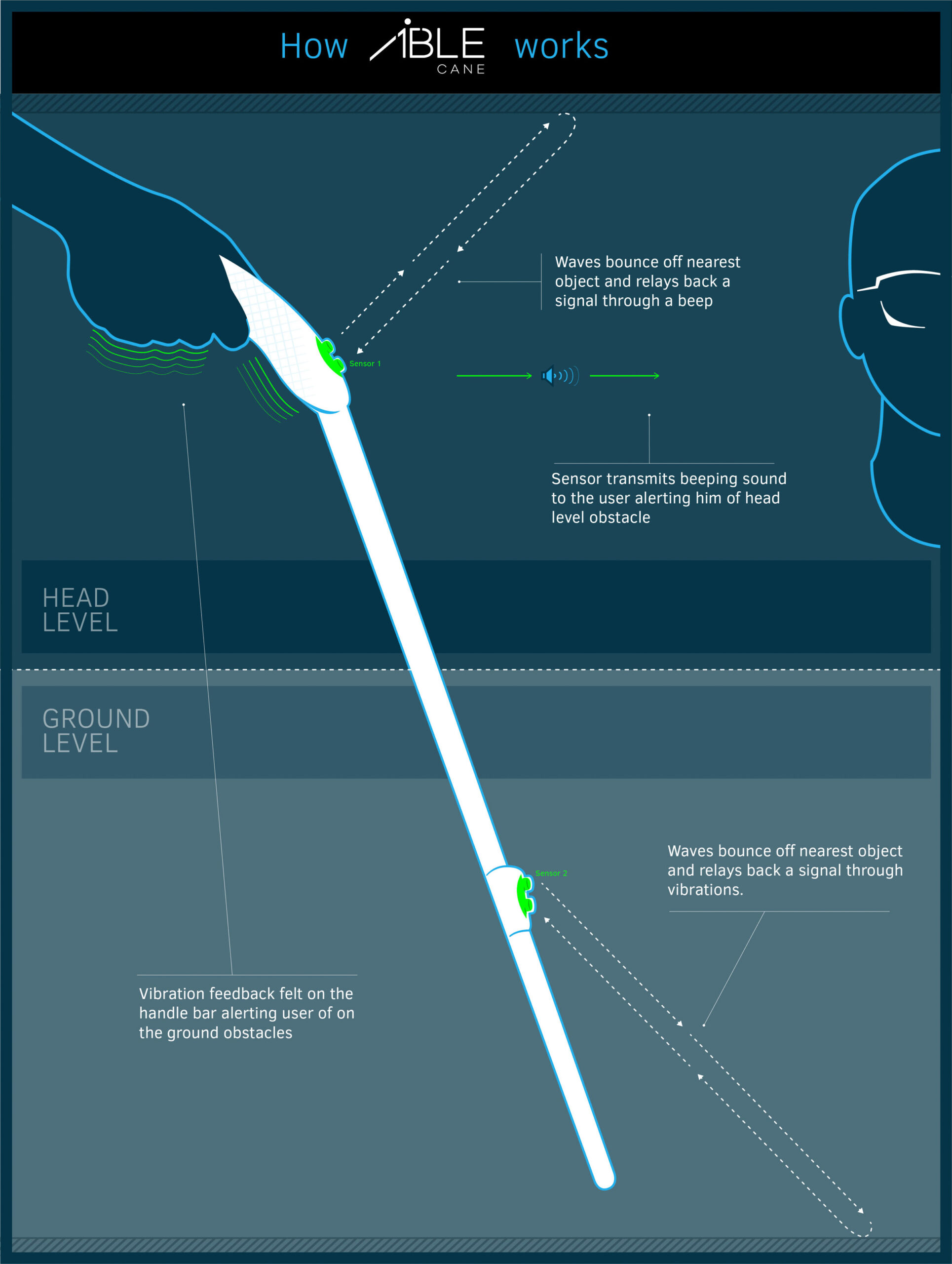

The SWC alerts users of impending obstacles through vibration and voice feedback. It is fitted with two pairs of sensors to achieve this. The head level sensors warn of obstacles that are at head level through a beeping sound. The knee level sensors warn of obstacles on the ground through vibration.

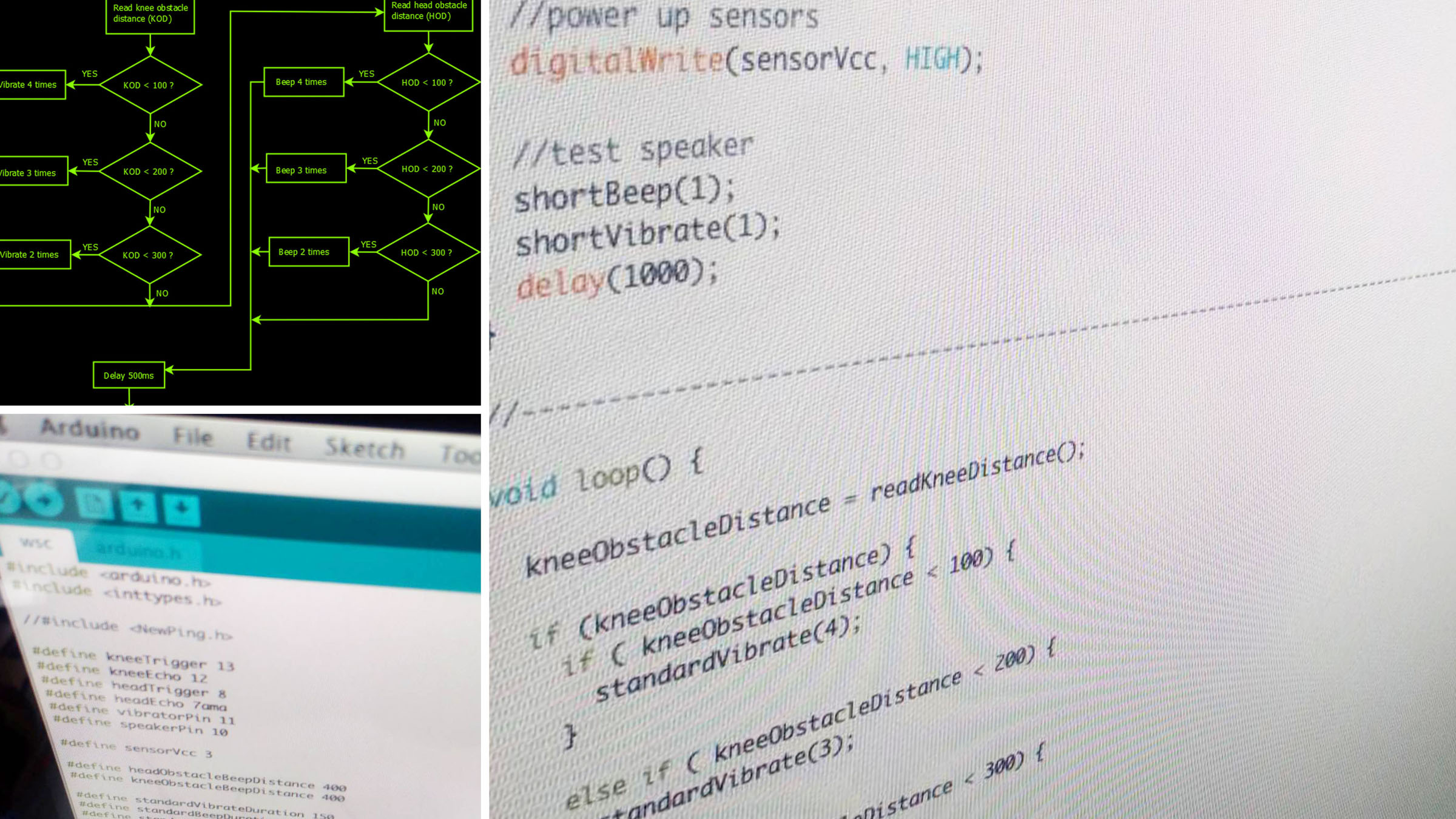

How it works

Head level sensors: depending on the distance from an object, users get different counts ofbeep signals.

< 100cm signalled by four beeps.

< 200cm signalled by three beeps.

< 300cm signalled by two beeps.

Knee level sensors: depending on the distance from an object, the SWC gives different vibration pattern signals:

< 100cm signalled by 4 short quick vibrations.

< 200cm signalled by 3 short quick vibrations.

< 300cm signalled by 2 short quick vibrations.

At the fortune of being obstacle free, a periodic, softer, short vibration occurs to reassure the user that the SWC is still ON.

The Brand

We needed to create a strong, humanised brand to represent the product, connect with its target audience and convey its positioning. The name Able Cane is simple, descriptive and positive in tone.

We took the opportunity to introduce symbolism in the wordmark. This gave the brand character and charm while reinforcing its purpose.